Ok. I have been meaning to post this for some time. I first discussed Haim Abitbol (also sometimes listed as Botbol, it changes from album to album) over a year and half ago. I then posted some information about him here.

The short of it is is that Haim Abitbol was born in Fez in the 1930s to a musical family. By the 1950s he was collaborating with Salim Halali and others. I picked up this cassette in 2009 in Casablanca and was blown away. Really great chaabi music. Many of Abitbol's albums appeared on the now defunct Koutoubiaphone label. He continues to perform to this day. Abitbol represents part of the long tradition of North African Jews performing unparalleled North African popular music. I digitized this cassette last week and I am providing the first track Toumobile jaya below. I will add the others soon.

Tuesday, December 21, 2010

A personal account of the funeral of Edmond Amran El Maleh

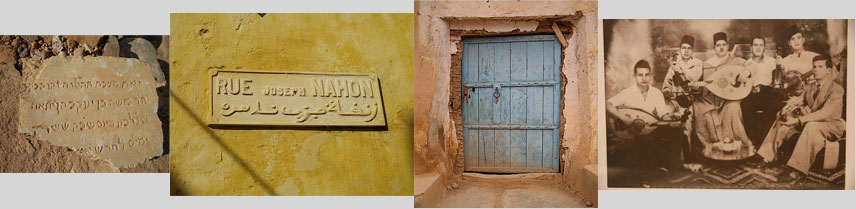

About a month ago, Megan MacDonald, a Fulbrighter in Morocco focusing on the role that Francophone / Moroccan novels play in Morocco and who is completing her dissertation on comparative literature at the State University of New York at Buffalo, contacted me about the death of Edmond Amran El Maleh and details for his funeral. Megan ended up attending the funeral in Rabat and wrote a beautiful piece (below). She also took some great pictures. I think these pictures speak volumes to complicated relationships in Morocco.

Megan MacDonald

20 December, 2010

mgn.macdonald@gmail.com

I first heard of the passing of Edmond Amran El Maleh at the age of 93, on Monday night via Twitter. Moroccan writer Laila Lalami reflected: “With the passing of Edmond Amran El Maleh, it feels as if a part of the literary, cultural (and yes, Jewish) history of Morocco has passed.” There was to be a tribute to this giant of Moroccan literature the next morning (Tuesday November 16, 2010) at the Jewish cemetery in Rabat, and then he would be brought to Essaouaira, his final resting place.

I wasn’t familiar with a Jewish cemetery in Rabat, so I turned to Google maps. I found two Jewish cemeteries in Rabat--one in between l’Océan and the Medina, and the other in Agdal. I emailed Chris Silver to ask him what he thought, having stumbled upon his blog while searching online for information on Jewish life in Morocco. My first instinct was that the older cemetery, the one near l’Océan and the medina, would be the spot for a tribute. In his email Chris reminded me “things in Morocco are never as they appear.” He also thought the medina would be the correct location. I asked IbnKafka on Twitter which he thought it would be. He was not aware of a Jewish cemetery in Agdal. I decided to ignore both of our first instincts, and head to Agdal. When I emailed Chris later on that day to tell him the cemetery was in Agdal he quipped, “Of course it was--I knew I should have trusted my opposite instinct.”

There were around one hundred people there milling about and talking in small groups when I arrived at 10am, with more trickling in over the next half hour. I heard a woman ask her companion in French, “Is the body here?” The crowd was made up of Moroccans and non-Moroccans, Muslims, Jews, Christians, those visually presenting as religious people, and those who were not, men and women, young and old, and several people wearing kaffiyehs with bright Palestinian flags on the borders.

The body was brought out, draped in a Moroccan flag, and everyone gathered around as prayers were sung and tributes made. A cameraman showed up, filming the speakers and the body. In the cement enclosure the emotional words of the speakers were occasionally broken up by shuffling feet, sniffling, and ringing cellphones. One speaker highlighted the Moroccan Jewish community, which he said must continue to live on, as he cited El Maleh’s support of the Palestinian struggle, and his desire that Palestinians and Israelis should live in peace. El Maleh was described as a man rooted in his history, a history of Morocco. A man of conviction who had fought against the French occupation in Morocco. The speakers expressed gratitude for El Maleh’s compassion, his willingness to listen patiently to questions from others--even if they were not ‘good’ questions, or ‘intelligent’ questions. A man of grace who respected others. A man characterized by an incredible dynamism and honesty.

Scholars write about El Maleh as someone who constantly challenged idées reçus and official histories through his fiction and other writing. These remain a testament to the memory of his disappearance, while also serving as texts that bear witness to historical memory, and to a re-writing of official and unofficial Moroccan histories. This work of excavation was also one of re-layering: pointing at pluralisms that have existed in Moroccan society while looking towards a future with one finger on these historical sediments. His literature re-examined forgotten realities of Moroccan history, doing so in a polyphonic manner. Writing in Le Magazine littéraire in March 1999, El Maleh put forth:

« Écrivant en français, je savais que je n’écrivais pas en français. Il y avait cette singulière greffe d’une langue sur l’autre, ma langue maternelle l’arabe, ce feu intérieur. »

El Maleh was man who leaves us with his writing, a body of work that will be there for our children, and for their children. A man whose work speaks to all Moroccans, described by one speaker as Berber, Arab, Jewish, Muslim, francophone, arabophone. He was, according to one speaker, a man who knew how to laugh.

As is the case with premonitions that reveal themselves clearly in hindsight, it is fitting to end with the words of El Maleh’s friend Abdellah Baïda, writing just before his passing in Le Soir: “Ce cher Edmond a encore des cartouches dans sa besace; on entendra certainement reparler de lui.”

For El Maleh’s part, he felt: "Quand je quitte le Maroc, je me déplace sans me déplacer."

References:

--Mary B. Vogl. “It was and it was not so: Edmond Amran El Maleh remembers Morocco” International Journal of Francophone Studies, 6 (2) 2003: 71-85.

--Edmond Amran el-Maleh, Le Magazine littéraire, mars 1999.

--http://www.aufaitmaroc.com/actualites/culture/2010/11/15/lettres-orphelines

--http://www.lesoir-echos.com/2010/11/05/edmond-amran-el-maleh-cette-obsedante-question-de-culture/

Megan MacDonald

20 December, 2010

mgn.macdonald@gmail.com

I first heard of the passing of Edmond Amran El Maleh at the age of 93, on Monday night via Twitter. Moroccan writer Laila Lalami reflected: “With the passing of Edmond Amran El Maleh, it feels as if a part of the literary, cultural (and yes, Jewish) history of Morocco has passed.” There was to be a tribute to this giant of Moroccan literature the next morning (Tuesday November 16, 2010) at the Jewish cemetery in Rabat, and then he would be brought to Essaouaira, his final resting place.

I wasn’t familiar with a Jewish cemetery in Rabat, so I turned to Google maps. I found two Jewish cemeteries in Rabat--one in between l’Océan and the Medina, and the other in Agdal. I emailed Chris Silver to ask him what he thought, having stumbled upon his blog while searching online for information on Jewish life in Morocco. My first instinct was that the older cemetery, the one near l’Océan and the medina, would be the spot for a tribute. In his email Chris reminded me “things in Morocco are never as they appear.” He also thought the medina would be the correct location. I asked IbnKafka on Twitter which he thought it would be. He was not aware of a Jewish cemetery in Agdal. I decided to ignore both of our first instincts, and head to Agdal. When I emailed Chris later on that day to tell him the cemetery was in Agdal he quipped, “Of course it was--I knew I should have trusted my opposite instinct.”

Exterior of Jewish cemetery in Agdal, Rabat (2010)

My taxi driver knew where the cemetery was, and asked me if I knew the word for cemetery in derija and fusha, which he promptly shared with me: (qbr) is a term in both derija and fusha that he said everyone would know, and (arodha) is specifically derija. He dropped me off at a semi-open gate, which turned out to be the cemetery for “the French”, according to the woman watching the door, with whom I exchanged some awkward derija, and which I later on found out is a Christian/European cemetery. She said that the Jewish cemetery was one door down.There were around one hundred people there milling about and talking in small groups when I arrived at 10am, with more trickling in over the next half hour. I heard a woman ask her companion in French, “Is the body here?” The crowd was made up of Moroccans and non-Moroccans, Muslims, Jews, Christians, those visually presenting as religious people, and those who were not, men and women, young and old, and several people wearing kaffiyehs with bright Palestinian flags on the borders.

The body was brought out, draped in a Moroccan flag, and everyone gathered around as prayers were sung and tributes made. A cameraman showed up, filming the speakers and the body. In the cement enclosure the emotional words of the speakers were occasionally broken up by shuffling feet, sniffling, and ringing cellphones. One speaker highlighted the Moroccan Jewish community, which he said must continue to live on, as he cited El Maleh’s support of the Palestinian struggle, and his desire that Palestinians and Israelis should live in peace. El Maleh was described as a man rooted in his history, a history of Morocco. A man of conviction who had fought against the French occupation in Morocco. The speakers expressed gratitude for El Maleh’s compassion, his willingness to listen patiently to questions from others--even if they were not ‘good’ questions, or ‘intelligent’ questions. A man of grace who respected others. A man characterized by an incredible dynamism and honesty.

Scholars write about El Maleh as someone who constantly challenged idées reçus and official histories through his fiction and other writing. These remain a testament to the memory of his disappearance, while also serving as texts that bear witness to historical memory, and to a re-writing of official and unofficial Moroccan histories. This work of excavation was also one of re-layering: pointing at pluralisms that have existed in Moroccan society while looking towards a future with one finger on these historical sediments. His literature re-examined forgotten realities of Moroccan history, doing so in a polyphonic manner. Writing in Le Magazine littéraire in March 1999, El Maleh put forth:

« Écrivant en français, je savais que je n’écrivais pas en français. Il y avait cette singulière greffe d’une langue sur l’autre, ma langue maternelle l’arabe, ce feu intérieur. »

El Maleh was man who leaves us with his writing, a body of work that will be there for our children, and for their children. A man whose work speaks to all Moroccans, described by one speaker as Berber, Arab, Jewish, Muslim, francophone, arabophone. He was, according to one speaker, a man who knew how to laugh.

As is the case with premonitions that reveal themselves clearly in hindsight, it is fitting to end with the words of El Maleh’s friend Abdellah Baïda, writing just before his passing in Le Soir: “Ce cher Edmond a encore des cartouches dans sa besace; on entendra certainement reparler de lui.”

For El Maleh’s part, he felt: "Quand je quitte le Maroc, je me déplace sans me déplacer."

References:

--Mary B. Vogl. “It was and it was not so: Edmond Amran El Maleh remembers Morocco” International Journal of Francophone Studies, 6 (2) 2003: 71-85.

--Edmond Amran el-Maleh, Le Magazine littéraire, mars 1999.

--http://www.aufaitmaroc.com/actualites/culture/2010/11/15/lettres-orphelines

--http://www.lesoir-echos.com/2010/11/05/edmond-amran-el-maleh-cette-obsedante-question-de-culture/

Labels:

Cemetery,

Edmond Amran Elmaleh,

Rabat,

Wikimapia

Abraham Serfaty Eulogized in JTA

JTA is starting a new blog called the Eulogizer. The first eulogy was dedicated to Abraham Serfaty and others. Hopefully we'll see something on El Maleh soon.

APPRECIATION

The Eulogizer: Holocaust survivor, Florida businessman, Moroccan dissident, Israeli firefighter

By Alan D. Abbey · December 20, 2010

JERUSALEM (JTA) -- The Eulogizer is a new column (soon-to-be blog) that highlights the life accomplishments of famous and not-so-famous Jews who have passed away recently. Learn about their achievements, honor their memories, and celebrate Jewish lives well lived with The Eulogizer. Write to the Eulogizer at eulogizer@jta.org. Read previous columns here.

...Lifelong Moroccan dissident, anti-Zionist

Abraham Serfaty, a lifelong Moroccan dissident whose opposition to repressive governments led to exile and imprisonment, died Nov. 17 at 84, 10 years after returning to his homeland in safety.

Serfaty was born in Casablanca to a middle-class Jewish family originally from Tangier. He joined the Communist Party in 1944, returned to Morocco in 1949 after receving an engineering degree in France, and participated in the fight against French colonialism.

In 1952 he was arrested and exiled to France under house arrest by the colonial authorities for his role as a nationalist activist. He returned home in 1956, when Morocco became independent, and worked in high-level government positions until he was removed from office for showing solidarity with a miners' strike. In the late 1960s and early 1970s he collaborated on an anti-establishment magazine, which led to his imprisonment, torture and then exile.

In 1991, following a campaign that included appeals from Danielle Mitterrand, wife of the French president, Serfaty was released from prison after 17 years, but his Moroccan citizenship was revoked and he again was exiled to France.

King Mohammed VI pardoned Serfaty and reinstated his citizenship, and Serfaty returned home to a villa and a modest income in 2000. He was later appointed adviser to the Moroccan National Office for Research and Oil.

A Dubai newspaper called Serfaty "a thorn in the side of the authorities in Morocco, both during the days of the French protectorate … and, later, under the repressive reign of King Hassan II."

"Serfaty was an activist who dedicated his life first to the anti-colonial struggle and then against the anti-democratic regime of King Hassan II," Moroccan Human Rights Association vice president Amine Abdelhamid said.

Serfaty was an anti-Zionist Jew who demanded abolition of Israel's Law of Return and supported the creation of a Palestinian state. In one of his books, "Prison Writings on Palestine," Serfaty wrote that Zionism is a racist ideology. His other books included "Anti-Zionist Struggle and Arab Revolution" and "The Insubordinate: Jew, Moroccan and Rebel."

APPRECIATION

The Eulogizer: Holocaust survivor, Florida businessman, Moroccan dissident, Israeli firefighter

By Alan D. Abbey · December 20, 2010

JERUSALEM (JTA) -- The Eulogizer is a new column (soon-to-be blog) that highlights the life accomplishments of famous and not-so-famous Jews who have passed away recently. Learn about their achievements, honor their memories, and celebrate Jewish lives well lived with The Eulogizer. Write to the Eulogizer at eulogizer@jta.org. Read previous columns here.

...Lifelong Moroccan dissident, anti-Zionist

Abraham Serfaty, a lifelong Moroccan dissident whose opposition to repressive governments led to exile and imprisonment, died Nov. 17 at 84, 10 years after returning to his homeland in safety.

Serfaty was born in Casablanca to a middle-class Jewish family originally from Tangier. He joined the Communist Party in 1944, returned to Morocco in 1949 after receving an engineering degree in France, and participated in the fight against French colonialism.

In 1952 he was arrested and exiled to France under house arrest by the colonial authorities for his role as a nationalist activist. He returned home in 1956, when Morocco became independent, and worked in high-level government positions until he was removed from office for showing solidarity with a miners' strike. In the late 1960s and early 1970s he collaborated on an anti-establishment magazine, which led to his imprisonment, torture and then exile.

In 1991, following a campaign that included appeals from Danielle Mitterrand, wife of the French president, Serfaty was released from prison after 17 years, but his Moroccan citizenship was revoked and he again was exiled to France.

King Mohammed VI pardoned Serfaty and reinstated his citizenship, and Serfaty returned home to a villa and a modest income in 2000. He was later appointed adviser to the Moroccan National Office for Research and Oil.

A Dubai newspaper called Serfaty "a thorn in the side of the authorities in Morocco, both during the days of the French protectorate … and, later, under the repressive reign of King Hassan II."

"Serfaty was an activist who dedicated his life first to the anti-colonial struggle and then against the anti-democratic regime of King Hassan II," Moroccan Human Rights Association vice president Amine Abdelhamid said.

Serfaty was an anti-Zionist Jew who demanded abolition of Israel's Law of Return and supported the creation of a Palestinian state. In one of his books, "Prison Writings on Palestine," Serfaty wrote that Zionism is a racist ideology. His other books included "Anti-Zionist Struggle and Arab Revolution" and "The Insubordinate: Jew, Moroccan and Rebel."

Labels:

Abraham Serfaty,

JTA

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)