|

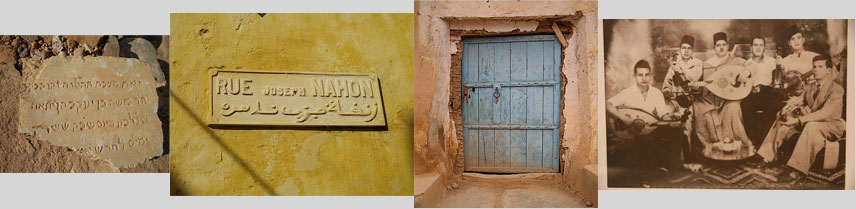

| Orchestre Raymond on Hes el Moknine. Mid-1950s. |

Nearly fifty-two years to the day, Raymond Leyris, known as

Cheikh Raymond on account of his mastery of the eastern Algerian Andalusian

musical tradition of malouf, closed his record store at 3 Rue Zévaco for the

final time. Within a year, Algeria would gain its freedom from France but at

that moment it was deep in the throes of a bloody civil war. With tensions

having already boiled over and almost a month after failed talks between the

French government and the Algerian Front de Libération Nationale (FLN), Cheikh

Raymond was trying to do the unthinkable as one of Constantine’s leading

professional musicians and a Jewish one to boot: He was attempting to lead a

normal life. After locking up at

Disques Raymond, he grabbed his daughter Viviane’s hand and headed toward Place

Négrier, home to the bustling Souq el-Assar and adjacent to the city’s Jewish

quarter, the Chara. Accompanied by his brother-in-law, the three casually

crossed the market place intending to lunch with Raymond’s uncle. Passing midway between the Sidi

el-Kettani Mosque on one side and the Jewish tribunal on the other, Viviane

noticed a man approaching. She

felt her father’s grip tighten. Within a moment he had collapsed. He had

suffered two gunshots to the neck at close range. The assailant escaped. Cheikh

Raymond was rushed to the hospital but it was too late. On June 22, 1961, at

the age of forty-eight, he was dead.

Cheikh

Raymond has long intrigued me. His story, little known outside the Maghreb and segments

of France, is riveting. Here are just some of the details. Raoul Raymond Leyris

was born in 1912 to a Jewish father and a non-Jewish mother, a rarity in

colonial Algeria. He was given up for adoption at the age of two and raised by

the Jewish Halimi family, who saw to his conversion. Raymond, as he came to be

called, gravitated ever closer to music in his teenage years. He sought out

authenticity, spending time in Constantine’s medieval foundouks, where he

apprenticed himself to the master musicians Omar Chaqleb and Abdelkrim

Bestandji. By 1928, Raymond had begun singing and playing oud with the celebrated

percussionist Mohammed L’arbi Benlamri, who would later join his orchestra, and

in 1930, he made his debut with Si Tahar Benkartoussa. By the age of eighteen,

the musical powers that be had bequeathed him the title of Cheikh.

|

| Sylvain Ghrenassia on violin and Cheikh Raymond on oud. |

While

paying allegiance to the traditional, Cheikh Raymond managed to do things his own

way. Interestingly, he seemed to have never recorded for the larger

international record labels. His first recordings were made in 1937 for the

Diamophone label, based out of Constantine, but World War II would soon put his

recording output on hold. In 1945, Cheikh Raymond formed Orchestre Raymond with

the Jewish violinist Sylvain Ghrenassia at his side. By the early 1950s, Cheikh

Raymond and Orchestre Raymond represented Constantine’s most sought after

Andalusian sound. It was also a fully integrated Jewish-Muslim ensemble. In

1954, at the start of the Algerian War, Cheikh Raymond and Sylvain Ghrenassia

expanded their business, founding their own record label, Hes el Moknine, and

opening a record store on Rue Zévaco.

In

the meantime, Gaston Ghrenassia, Sylvain’s son and the figure who would later come

to be known as Enrico Macias, had taken to seeing Cheikh Raymond as an uncle figure,

lovingly referring to him as “Tonton Raymond.” The younger Ghrenassia’s musical talent impressed Cheikh Raymond and he invited Gaston to join his

orchestra as a guitarist – bucking malouf norms at the time. Gaston made his debut with

Orchestre Raymond that same year.

|

| Cheikh Raymond at 78 rpm for Hes el Moknine. |

Cheikh Raymond released dozens of

78s for his Hes el Moknine label in the 1950s, although given the length of a

typical Andalusian movement, the format was far from suitable. It was thus with

great pleasure that he adopted the LP format, putting out two dozen 33 rpm

records in the same period and a similar number of EPs. He invited a few others

to record on his label as well.

Mal habibi malou was the twentieth release on his label. It represents one of the more

well-known Andalusian pieces and was recorded by nearly everyone worth their

weight in the music industry. Cheikh Raymond’s interpretation is

breathtaking. You get a real sense of his voice and his passion. Pay close

attention to the violin work by Sylvain Ghrenassia as well. This eighteen minute cut is taken from the original.

|

| Cheikh Raymond with Algerian Jewish star Sassi Lebrati. |

Cheikh Raymond and his orchestra gave their last large public

concert at the Vox Theater in Constantine in April 1960. In the fall, he made

his final television appearance, singing

Hokmek Hokm el-Bey, that old-new Andalusian song of Ottoman

resistance to the 1830 French invasion and which now carried contemporary nationalist

overtones. His political stance, the subject of much speculation, seems to be

clear in this instance.

Yet, in January 1961, during a short visit to

France, rumors about Cheikh Raymond surfaced. He was accused by unknown

elements of belonging to the OAS. In another version, he was to have moved to

Israel. Neither of course was true and neither could have been farther from

reality. In fact, Enrico Macias recalls Cheikh Raymond telling him at the time,

“I would rather die in Algeria than live in France.”

On June 22, 1961, two bullets struck Cheikh

Raymond as he walked through the crowded markets of central Constantine. There

were plenty of witnesses but no arrests. Cheikh Raymond was rushed to the

hospital, the same one where he had been delivered and then given up for

adoption decades earlier. He was pronounced dead on arrival. In accordance with

Jewish custom, Cheikh Raymond was buried in Constantine’s Jewish cemetery the

next day. In July 1961, the Leyris and Ghrenassia families arrived in

Marseille. Despite pleas to transfer her husband’s remains to France, Hermance

Leyris refused. Cheikh Raymond would remain once and forever in his beloved

Constantine.

There is much commentary to add to this story but I will try to keep it

short. Cheikh Raymond’s murder remains unsolved to this day although FLN

participation seems likely. In the course of the turmoil of 1961 and 1962, the

perpetrators were never caught and the case was never brought to trial. Names,

motives - the answers - are buried probably not too deep in an Algerian archive

somewhere. Both scholars and popular observers agree that the death of Cheikh

Raymond triggered the flight of Constantine’s roughly 30,000-strong Jewish

community to France.

The figure of Cheikh Raymond continues to loom large in the

Constantinois Jewish collective memory, with former residents marking their own

histories as before and after June 22, 1961. So too do memories remain vivid

among Constantine’s Muslim population, especially music aficionados. At least

two individuals have worked hard to commit Cheikh Raymond’s memory to history:

Enrico Macias, his son-in-law and Francophone variety singer, and Taoufik

Bestandji, the grandson of Cheikh Raymond’s mentor Abdelkrim Bestandji and an

accomplished musician in his own right. Much of what we know of Cheikh Raymond

is thanks to them and countless other individual recollections.