|

| Samy Elmaghribi and Salim Halali are still played at the Astor, Fez's last kosher restaurant and bar |

|

| Hadj Belaid fresco in Tafraoute (2012) |

Some three years after first discovering the magic of

musician Haim Botbol in a record store in Casablanca, I returned to Morocco to

find his music in cassette stalls across the country. In fact, I got an even

deeper sense of the critical importance of music in the Maghreb on this trip.

In Tafraoute, in the country’s deep southwest, frescos of musical instruments

like the rebab and images of musical standouts from the 1940s like Hadj Belaid

adorned walls throughout the region’s ancient villages. At a pizza joint along

the Tizi-n-Tichka pass, a banjo on a chair was displayed prominently. When the

restaurant’s owner wasn’t making pies, he would strum a few chaabi notes. And

in Casablanca, by the former Lincoln Hotel, a cd seller played Samy

Elmaghribi’s version of Gheniet Bensoussan for passersby.

After years of collecting Moroccan and then North African

music in general, I was interested in not only finding dusty recordings from

Tangier to Fez but also to collect musical memories. I was interested in how

Moroccans, Jews and Muslims, understood and remembered their Jewish pop icons

of yesteryear and so I went looking.

I started in Tangier and found very little. I figured a

Mediterranean port city with a once large Jewish community would herald in an

auspicious beginning. Being there during Ramadan hampered my efforts in many

ways. Most medina shops were closed during the day. A general lethargy had set

in. Additionally, Marcel Botbol’s music club, just outside the medina, was

closed and I soon learned he was switching venues but wasn’t due to reopen

until the following month. Undeterred, I kept searching. Walking up and down

medina thoroughfares and side streets, I finally happened on a store selling

clocks that a friend had mentioned. A half dozen sun faded Mohammed Abdel Wahab

LPs were displayed prominently in the window. He must have had more stock, I

thought. He did but he was too tired, he told me. I pressed him but I decided

to let it go. Considering that he had been holding on to records for some

thirty years past their utility and interest for most people, I could

sympathize with his exhaustion. Besides, there would be other opportunities.

|

| The interior of Le Comptoir Marocain de Distribution de Disques (2012) |

Where Tangier yielded little, Casablanca was a black gold

mine. I returned to the places which had launched this musical journey for me

three years ago: Le Comptoir Marocain de Distribution de Disques on Lalla

Yacout and Disques Gam in the opposite direction on Boulevard de Paris. At Le

Comptoir, also the home to the Tichkaphone label, I snagged a dozen Botbol

cassettes. It’s safe to say that Le Comptoir represents one end of the record

store spectrum, organized and immaculate, whereas Disques Gam is the other end,

chaotic, hot as hell, and magnificent. Gam Boujemma is the store’s proprietor

and a repository of musical knowledge. You have to know what you’re looking for

here and I did. With every record or cassette he pulled out, I was deluged with

hard to come by oral history. Stories of Samy Elmaghribi performing at the

nearby Cinema Lux fascinated me. As did his reverence for Albert Suissa. I

walked away with a few prize items from his archive including a couple EPs on

the N. Sabbah label and Botbol’s only release for Philips.

|

| Two Giants: Albert Suissa on N. Sabbah and Botbol on Philips (2012) |

In Morocco, the musical medium of choice corresponds

directly to the seller’s knowledge of the industry. Those selling records

should be placed at the top of the hierarchy, followed closely by cassette

purveyors and CD distributors a distant third. Also, a couple things happened

in Morocco in the 1970s that should be noted. One, the music industry was

nationalized. Two, cassettes appeared, allowing records to be transferred

directly to tape and distributed widely. The era also represents one of the

last gasps of the prominence of Jews in the Moroccan music scene.

Janatte Haddadi's beautiful short on Coq d'Or

The Casa medina was once a musical mecca for Moroccan Jews.

It was here where Salim Halali’s club Coq d’Or, now a textile factory, once

stood. Albert Suissa continued to live and write music in the mellah until a

late age. So I was elated when I stumbled upon one of the remaining few cassette

sellers in Casa’s medina. His stall was impossibly tiny. Floor to ceiling tapes

lined its walls. With my eyes quickly scanning the now all too familiar

artists, I noticed something peculiar. In his collection were dozens of Israeli

releases of Moroccan Jewish artists from the Holy Land. While the Zakiphon

labels had been removed, these were clearly Jaffa-based releases of Cheikh

Mwijo, Raymonde, and Sliman Elmaghrebi. Here was evidence of a fascinating

chapter of music moving beyond closed borders.

|

| Found: Samy Elmaghribi in a Casa cassette seller's attic (2012) |

I told him what I was looking for and he had everything. I

walked away with long sought after Felix El Maghrebi and Zohra El Fassia tapes complete

with hand written song titles. On a whim, I asked if he still had records.

Without flinching he took a rickety ladder and propped it against a wall of

cassettes and started climbing towards his attic. He pulled down two large bags

of 45s. I started to comb through them as my heart raced. What would I find?

The occasional Samy Elmaghribi EP surfaced as did the odd Botbol cover

(including an Algerian release) but unfortunately none of the covers matched

the records and none of what he had was what I was looking for. Despite this, I

had learned a great deal in this encounter.

|

| Hadj Belaid recording on Baidaphon c. 1940s |

Before finally heading to Fez, I spent a week with my

girlfriend and friends traveling in the Marrakesh area and to its east. Toward

the end of the week, we visited the village of Telouet, home to a breathtaking

Glaoui casbah. As we left, it started to drizzle and then pour. A nearby café

provided us shelter and piping hot mint tea. On our way in I had noticed a 50s

era HiFi system at the entrance. Where there was a record player, I thought,

there must be records. I started asking the right questions. Within a moment my

hosts informed and then showed me that it still hummed along, in fact, it

played beautifully. They put on a couple of Western LPs and then brought out

two black plastic bags of 78s. These were all priceless 1940s recordings of

Hadj Belaid on Pathé and Baidaphon. We were all having a great time. A waiter

took a lighter to one of the records to show me this was no plastic we were

dealing with. This was shellac! Handshakes were had all around and then I

excused myself to finish my tea.

|

| Le Cristal in Fez, still bustling (2012) |

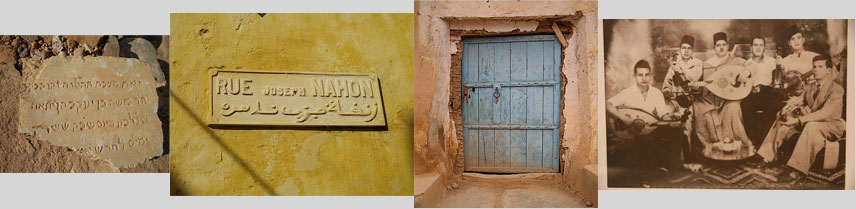

My last few days in Morocco were spent in Fez. For the first

time, I stayed in the Ville Nouvelle. I was captivated. For the tourist and the

historian, some of the beauty of Morocco, even in its “modern” counterpart to

the medina, is the (at least superficially) unchanging landscape and

architecture. Thus my hotel in Fez was located right next to the now defunct

Astor Cinema, which was next to the still in operation Astor Bar (home to Fez’s

remaining kosher restaurant) and a stone’s throw a way from independence era

café’s like the Cristal. You quickly started to get a feel for what Jewish Fez

must have looked like in the 1950s and 60s.

I was not disappointed by what I found in Fez’s medina. After

paying homage to the record-turned-cd label Fassiphone, right outside the old

walls, I launched myself into the city’s infamous myriad alleyways. It was not

before long before that I located the cassette district. One seller’s stash of

Jewish musicians was significantly reduced. About seven tapes were all that

remained. He was eager to sell, including what appeared to be his most

master-like recordings, but I held off.

|

| Botbol, tea, and towers of tapes in Fez (2012) |

A twist and a turn later and I had found my man. “Mohammed”

cut a handsome figure against a background of thousands of tapes. He saw me

staring and ushered me “in.” A dozen pleasantries later, short introductions, a

sip of wormwood infused tea, and the cassettes jumped one after one into the

tape deck. Mohammed was a former musician and played often with his Jewish

counterparts. His familiarity with the scene was astonishing. When I asked

about Botbol, Mohammed mentioned he knew Jacob, the father, and then dutifully

put on a recording, which he sang every word to. This pattern of singing along

with the uttering of an artist’s name repeated itself with a range of

performers from Cheikh Mwijo to Samy Elmaghribi. The mere mention of Zohra El

Fassia, the grande dame of Fez, brought a large smile to his face. He started

recalling the heyday of places like the Astor and Cristal and others. I

couldn’t resist, I bought way too much from him but it was worth it. He then

took us to his gorgeous medina home for another cup of tea. His roof view

rivaled any in the city. I asked him to see pictures but instead I got his

address with a request to keep in touch. I couldn’t have been happier to

oblige. Mohammed wasn’t sure if anyone still sold records in Fez but

I was happy nonetheless. Not everything has been transferred to CD so getting

your hands on tapes is the next best thing.

|

| Prized records including Botbol, bottom row (left) (2012) |

|

| Zohra El Fassia on Polyphon c. 1940s (2012) |

I took the long way out of the

medina and I’m glad I did. A few missteps and backtracks later and I had

located what may be Fez’s last record store. The owner, much older than

Mohammed, was also a former musician. Hundreds of records were arranged in some

of the most creative ways I had ever seen. He displayed his most prized

records, including a not-for-sale Botbol, on one side of the store. At his desk

were beautiful black-and-white and sepia photos of his former life. Behind him

were cassettes of Morocco’s most influential stars including Samy Elmaghribi,

whom the proprietor called the best Isra’ili singer in Moroccan history. I

painstakingly combed through piles of LPs and EPs and pulled out impossibly

difficult to find cuts. As I continued to look high and low for records, which

seemed to be hiding everywhere, I saw a dozen 78s in the corner. I gently

removed them from the shelf. Sifting through these treasures one by one, my

heart skipped a beat. There it was…a 70-year-old recording of Cheikha Zohra El

Fassia made for the Polyphon label. I showed it to the owner. He put on his

glasses and said zeena (beautiful). Sadly, the record itself was beyond playing

condition but its near forgotten presence in this store still sings volumes to

me.